Total Football Analysis

·26 October 2020

La Liga 2020/21: Barcelona vs Real Madrid – tactical analysis

Total Football Analysis

·26 October 2020

This tie was the first Clásico in 17 years in which both sides went into the clash having lost their last league game. Defeat to Cádiz had been compounded for Real Madrid as they were beaten by Shakhtar Donetsk, meaning that crisis talk was all over the place as they travelled to face a Barcelona side who have spent months in turmoil, capped by defeat to Getafe a week before meeting their arch-rivals.

It was Real Madrid who got off to the perfect start as Fede Valverde opened the scoring, with Ansu Fati hitting back immediately in a far more open and explosive beginning to the game than expected. A penalty scored by Sergio Ramos and a third added by Luka Modrić sealed the victory.

This tactical analysis of El Clásico will look at the tactics of Ronald Koeman’s Barcelona and Zinedine Zidane’s Real Madrid. The analysis will highlight the key factors that led to the victory for the visitors, giving them a clear advantage over their La Liga counterparts in the race for the title.

Koeman made gambles with his team selection as consistent, if not spectacular, performers like Sergi Roberto and Antoine Griezmann were dropped, with Jordi Alba coming back into the side after an injury lay off and Sergiño Dest getting his first start in his preferred right-back role since joining from Ajax. Neto kept his place in goal, with Gerard Piqué and Clement Lenglet selected in defence. In midfield, the shape altered between a 4-2-3-1 as seen so far this season, and a 4-4-2, which allowed greater freedom to Ansu Fati to run in behind while Lionel Messi dropped deeper. This system didn’t suit Messi greatly, as will be covered later, with Philippe Coutinho and Pedri drifting into central areas ahead of Sergio Busquets and Frenkie De Jong. The headline, however, remained the selection of two 17-year-olds for a Clásico for the first time since 1947.

Real Madrid, on the other hand, stuck to what Zidane knows. Thibaut Courtois in goal had demanded defensive solidity before the game and so it came as excellent news that captain Sergio Ramos was fit, having been forced off against Cádiz and missed the defeat to Shakhtar Donetsk. He played alongside Raphaël Varane in the middle, with Ferland Mendy’s defensive consistency prefered to Marcelo on the left and with Nacho filling in for the injured Dani Carvajal on the right. In midfield, Valverde’s energy gave him the nod alongside Toni Kroos and Casemiro ahead of Modrić, with the recent first-choice front three of Vinícius Júnior, Marcos Asensio and Karim Benzema keeping their places in a shape which resembled 4-3-3 in possession and 4-1-4-1 out of it.

The earliest stages of this encounter were dominated by the way in which the game bypassed the midfield. With defensive frailties on show, as will be highlighted later, quick transitions and long balls would see the two midfields almost taken out of the equation for the first 10 minutes. Then, keen to stabilise and slow the pace down, as evidenced by the 19.8% reduction in the total number of passes made in the second 15 minutes of the tie, compared to the first 15 minutes, and this meant we saw the midfield come more and more into the tie, suiting Real Madrid down to the ground.

The first way that Real Madrid looked to do this was by having a narrow midfield three which would effectively look to block out the central Barcelona trio of De Jong, Busquets, and Fati or Coutinho in the central role. Casemiro would take the more offensive man, with Kroos and Valverde picking up the other two players. This left Vinícius and Asensio to pick up the slack of the wingers, providing cover for Nacho or Lucas Vázquez and Mendy. This enabled Real Madrid to form deep defensive blocks in two lines, but keep pressing Barcelona to stop them from advancing. Not since the Champions League defeat to Manchester City had a greater percentage of recoveries been made in the low block than 54.5%, but that fed into Real Madrid’s approach, allowing Barcelona to hold possession until they broke into the final third.

This structure also extended to when Barcelona did push forward in numbers. Casemiro would drop into the central defence, particularly with Ramos stepping up to press, and Kroos or Valverde would still replicate the same role of pressing slightly higher in order to press and cancel out the move before it could progress. The deep positioning of Vinícius and Asensio meant that Barcelona simply could not find a way through and despite dominating possession peaking at 63% in the early stages of the second half.

On the ball, Real Madrid were able to use this to suit them. One-on-one in midfield positions and with Casemiro free of too much pressure, they could play out and around the midfield trio quickly. By bypassing Busquets and De Jong, Real Madrid were able to join Napoli and Bayern Munich in becoming the third team to beat Barcelona for possession in 2020. They effectively moved the ball into wide areas, where a rapid counter transition could be managed, or the ball would be returned into a central role where the midfield could again dictate play.

This midfield domination was essential and necessary to Zidane’s reaction. It came as a result of the opening minutes and much of the first half where Nacho in particular looked vulnerable. This reflected how Real Madrid initially struggled to handle the pace and energy of Barcelona, particularly in wide areas. Koeman was clearly looking to focus upon Nacho on the right of the Real Madrid defence, much like Cádiz had only a week before, with 45.9% of positional attacks coming down the left flank. Jordi Alba led the way here, pushing at pace, while Coutinho, Fati, or Pedri would look to force Nacho or a midfielder to step up. De Jong was particularly effective at this, holding position deep, inviting Nacho to step up.

Once he did, Jordi Alba would burst down the left and Fati would be monitoring closely in order to explode into a burst of pace. Early on, this caught Real Madrid out, particularly Ramos, who struggled to turn at pace and keep up with the 17-year-old. This meant that Jordi Alba could do what he does best, attacking at pace then cutting back from the byline, setting up Fati to tap in having left Ramos and even Varane for dead.

This was indicative of how Barcelona looked to exploit Nacho and his role on the right of the Real Madrid defence. With Ramos unable to cope with Fati’s pace, the side immediately resorted to playing with a deeper defensive line in order to limit the potential for the youngster to attack at pace through the middle. Attacks still came down the flank, but were not quite as clinical as Fati found himself running into a brick wall of defenders, rather than into space to convert an easy chance.

Another key turning point in the tie was the introduction of Vázquez. Defensively, he has never been the most reliable of options, acting more as a wing-back than a full-back, but against Barcelona he showed great discipline. He held his position remarkably well and engaged in nine defensive duels, only surpassed by Kroos and Casemiro, despite not playing the majority of the first half. What’s even more impressive was that only Ramos and Varane won a higher percentage than his 56% success rate.

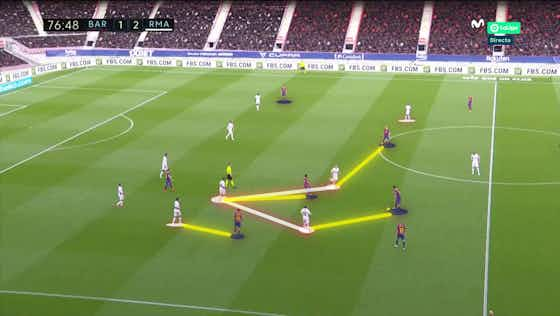

Beyond simply introducing Vázquez, Zidane also altered his team’s approach. The team also looked to defensively overload their right-hand side whenever Barcelona looked to switch possession to the left. With support from Valverde and Asensio, often helped by further support from attack, they would look to stop attacks from progressing beyond Barcelona’s deep midfielders. It denied space to Jordi Alba who would look to run into the gaps left in behind, and slowed down Barcelona’s transition significantly. That frustrated Barcelona, forcing them into slower transitions and switching the ball across to the right.

However, to discuss only the structure of Real Madrid in which Vázquez formed a part would be to do him a disservice. Despite his lack of experience at right-back, accounting for just 893 minutes, or 0.07% of his game time, in that position since he joined Real Madrid in 2015, he reacted well. When Barcelona did find space on their left, with space opening up as Asensio tired and tracked back less, he would occasionally step up before reverting back, as in this example above. Identifying the space he would be leaving in behind for Coutinho or Jordi Alba, he would revert to sitting back deep and allow one of the dropping midfielders to handle the pressing Barcelona rival coming from midfield.

Ironically, many of the issues that Barcelona looked to cause Real Madrid were also evident in their own defence. With Alba pressing high to look to counter on the attack, or even just pressing high as he likes to with his high pressing approach, spaces would open up which Asensio and Benzema would look to attack. By doing so, Barcelona’s defence would be dragged across, with Lenglet forced to cover and Piqué being forced across too to pick up Benzema. With Dest preoccupied covering Vinícius and his pace down the flank, it meant that spaces were opening up in central areas.

Real Madrid looked to transition quickly, just as Barcelona did. In these early stages, that was easy, as neither De Jong nor Busquets could match the pace of Valverde’s central runs. This meant that as Asensio pulled Lenglet wide and Piqué picked up Benzema, there was a space in the middle for Valverde to run into which Busquets would not be able to follow him into. With two simple passes, from Nacho to Benzema and then from Benzema through the middle into Valverde’s path, Real Madrid had gone from their own defensive third to a one-on-one situation against Neto.

These spaces continued to open up throughout the tie. Real Madrid did not capitalise as much on them until late on when Rodrygo Goes was introduced, as they looked to slow down the pace of the game and dominate through possession or only allowing Barcelona to have non-dangerous possession. Spaces continued to open up, with Valverde continuing to exploit, but he would become more conservative, preferring to form part of the defensive structure or avoid risk than to gamble on a breakthrough in Barcelona’s shape.

As has already been discussed, much of Barcelona’s threat came down the left. However, very little of it came through Pedri. Jordi Alba required space to run down the flanks on the left, forcing Pedri to drift further infield and cut inside into a position that he is less comfortable with. Such a role would have been more naturally suited to Griezmann, yet he only got a late run-out against a team who, by that stage of the game, were sitting very deep and denied him any space to move into.

As Real Madrid built a structure, it only served to further silence him, touching the ball in the box on just two occasions. Barcelona became keener to keep the left flank as clear as possible for Jordi Alba to exploit any space that could open up. That left Pedri in a dead area of the field, as reflected below. Receiving the ball and given the difficult task of beating Vinícius for pace while Kroos supported him, he would not have found space to run into even if he had given how close together the Real Madrid lines were, with Messi and Fati also floating in the space between the two lines.

This was also partly behind the role of Messi. Quieter than ever, he registered 0 expected assists for only the fifth time in 2020, and just 0.43 xG – his lowest figure in five games. Without space to operate in between the lines, Real Madrid silenced him effectively just as they did Pedri. With Pedri drifting to the right and Coutinho doing the same, in only served to add to the congestion and make Messi’s most natural areas even more turgid. No longer able to engage in the high-speed counters and transitions as naturally as he once was, that role now falls to Fati, and in this case, Messi was denied the space to influence play as a playmaker.

This was a back to basics approach from Zidane, while Koeman gambled. That gamble backfired. Real Madrid were confident and committed in their approach, while Barcelona looked lost at times, struggling to create space in the right areas and becoming predictable with their constant preference to go down the left on quick counters, or down the right when looking to break play down.

As such, Real Madrid had an easy task to defend against Barcelona. On the counter, they found it easy to create space and open up the Barcelona defence. Busquets’ lack of mobility and pace meant that the defence was exposed, with midfield runners and wingers able to generate space for others to run into.

What effectively decided the tie though, was the reaction of each coach. As can be seen in this analysis, Zidane learnt from Real Madrid’s early mistakes, dropping his defence into a deeper line and overloading the right by bringing in Vázquez. Even after that, he identified the lack of spaces opening up and a tiring Barcelona defence, so brought on Rodrygo to attack those as the team had early on, with Modrić making Valverde’s runs. That’s exactly how the third goal came about. On the contrary, Koeman did not make a change until the 82nd minute. By then, Real Madrid had made three and were leading. Those changes were simply too little too late and did nothing to correct the issues with Barcelona’s system. The result was a convincing victory for Real Madrid.

Live