Total Football Analysis

·22 September 2020

Premier League 2020/21: Chelsea vs Liverpool – tactical analysis

Total Football Analysis

·22 September 2020

Liverpool continued their Premier League title defence with another tough battle. After hosting Marcelo Bielsa’s Leeds United at home, they had to travel to London to face Chelsea at the Stamford Bridge. Both teams last met just about two months ago, with the Reds came out victorious in the 5–3 thriller.

This game, however, didn’t produce as many goals as the previous meeting. Yet, it still displayed interesting tactical battles as well as dramatic turns and twists throughout the 90 minutes. At the end of the day, Liverpool prevailed once again and successfully continued their positive start in their title defence. Without further ado, this tactical analysis will inform you how did Liverpool achieve the convincing 2–0 win.

Frank Lampard chose 4–3–3 for his team. The duo of Andreas Christensen and Kurt Zouma started at the heart of the defence, while Jorginho provided cover in front of them. In the frontline, new recruit Kai Havertz and Timo Werner were supported by Mason Mount as the Blues’ attacking trident. Names like Ross Barkley, Tammy Abraham, and Fikayo Tomori had to start the match from the bench.

In the opposite side, Jürgen Klopp also went for 4–3–3. The back-four consisted of Trent Alexander-Arnold, former Real Madrid player Fabinho, Virgil van Dijk, and Andrew Robertson. Meanwhile, the firing line was spearheaded by the trio of Mohamed Salah, Roberto Firmino, and Sadio Mané. Liverpool’s bench was filled with players like Takumi Minamino, James Milner, and multiple Champions League winner Thiago Alcántara.

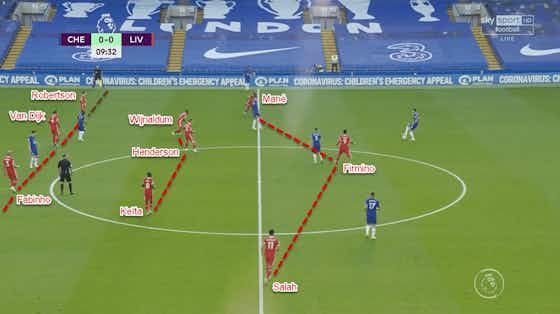

This analysis will start by examining Liverpool’s defending tactics. Structure-wise, they used a (lopsided) 4–3–3, which sometimes could also be seen as a 3–4–3. We will dissect the details later.

In the first pressing line, Liverpool kept their attacking trio intact. However, Firmino had a different task to the wingers. As a centre-forward, Firmino was tasked to close down Jorginho. If Jorginho didn’t drop to the 16-yard line, Firmino would close him by using his cover shadow. However, if Jorginho did drop, Firmino would stand about one or two metre(s) behind him. The objective of this was to prevent Jorginho from receiving the ball in Chelsea’s early build-up phase.

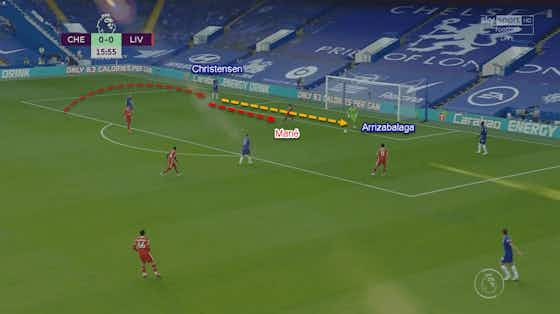

Alongside Firmino, the wingers had a similar task. They were tasked to stand just outside the penalty box (in the half-space) and press their ball-side centre-back when the ball was played short. It means if Kepa Arrizabalaga passed the ball to Christensen, Mané would press. If Zouma was the short target, then Salah would come to shut him down.

However, they didn’t just press. Both Salah and Mané would curve their run when trying to close down Chelsea’s centre-backs. This would prevent Christensen and Zouma to pass to their full-backs because the Liverpool wingers would close the passing lane with their cover shadows. This would also limit the space for the on-ball defenders as they would be forced to play centrally.

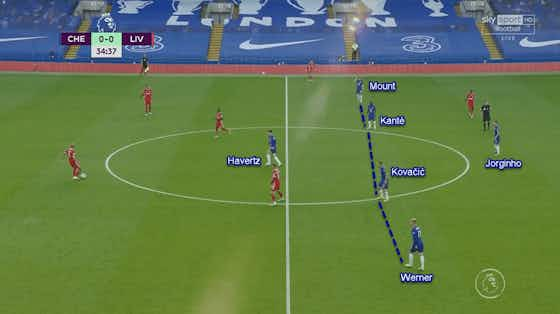

Now let’s talk about the details. The lopsided shape could be seen in Liverpool’s second pressing line. First of all, this part happened because of Chelsea’s build-up scheme. The Blues would allow one midfielder — Mateo Kovačić — to drop from his position and help the deeper players in their build-up. Liverpool reacted to this by sending Naby Keïta to step up and stand close to the Croatian.

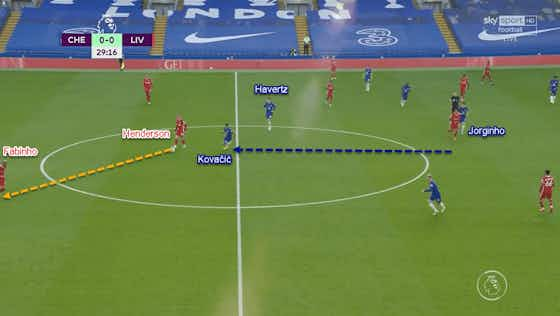

Different treatments could also be seen to Chelsea’s full-backs. In the left flank, left-sided central midfielder Georginio Wijnaldum would be tasked to step out and press Reece James if the ball was played to the right-back. The Dutch’ movement then would be followed by the defensive midfielder Jordan Henderson. Henderson would drift to the half-space to follow and press N’Golo Kanté; James’ nearest progressive option. This pressing scheme almost bore its fruit as it led to Liverpool’s biggest chance in the first half.

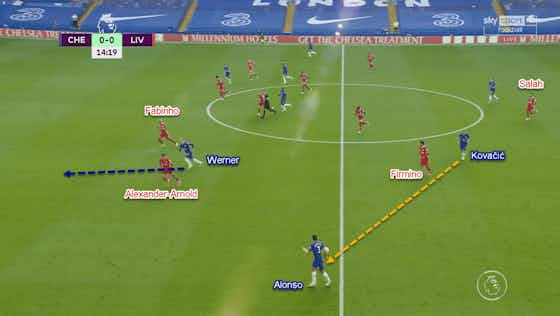

Now we move to the opposite side. In the right-flank, Liverpool somehow gave Alonso more space. Their right-back Alexander-Arnold would stand a bit behind his midfielders and would only press Alonso when the ball has arrived to the Spaniard. The remaining defenders — Robertson and the centre-backs — stayed in the halfway line to engage in aerial duels whenever needed.

Liverpool’s aggression could also be found when defending in deeper areas. When they allowed Chelsea to have possession, Liverpool would defend in a vertically compact mid-block 4–3–3 or 4–5–1. By defending in a very compact manner, Liverpool prevented the Blues to play in between the lines. Their mid-block defensive system wasn’t only about the compactness, though. They also deployed a very high-defensive line and occasionally used offside-traps to limit Chelsea’s threats.

The Reds were not just defending passively and sit in the halfway area. Instead, they would use a ball-oriented press, particularly against Chelsea’s midfielders. It means that either Keïta, Henderson, or Wijnaldum would step up from the midfield line and pass the on-ball Chelsea midfielder, even when the ball was still on its way. The objective was to limit Jorginho or Kovačić’s time and space with the ball; thus preventing them to control the possession.

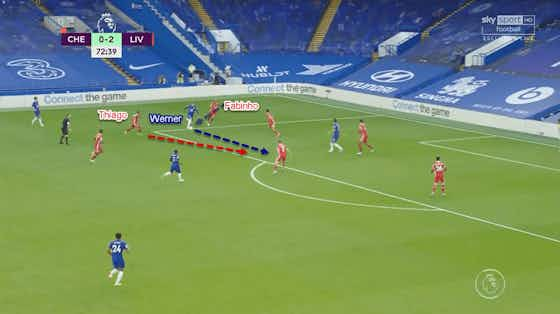

The Blues noticed Liverpool’s high defensive line and did try to exploit that. However, some problems that occurred in their attempts. Before we get deeper on that, let’s dissect the general ideas in Chelsea’s tactics against the aggressive defensive line. Mainly, Chelsea would try to attack from the left flank, probably because of Salah’s relatively low defensive workload compared to his attacking partners. Another reason was that they could utilise Werner’s pace in the left-flank against Alexander-Arnold and Fabinho.

The first way Chelsea could exploit that was by finding Alonso free in the left flank. After that, the Spaniard would be tasked to find Werner in behind with incisive through-balls. The German himself would start his run between Alexander-Arnold and Fabinho (in the half-space) to confuse them on who to close him down. However, Alonso didn’t do his job properly. The stats showed that he only made four (50%) accurate progressive passes throughout the game. Surely not enough to break Liverpool down.

Another way Chelsea used to exploit the high defensive line was by sending aerial balls; using the deeper players as their distributors. This approach wasn’t only about Werner, though, as Chelsea could also try to find Mount, Havertz, or even Kanté in behind. However, they lacked quality in their deliveries. Sometimes the lofted balls were way too hard for the attackers to chase. In other occasions, the passes were too short and didn’t even reach Liverpool’s final third.

Despite the lack of chances created by the home side, some positives can be taken from this game. That mainly being Werner’s presence and quality in Chelsea’s attacking line. From time to time, his speed and driving ability was crucial for the home side in creating chances.

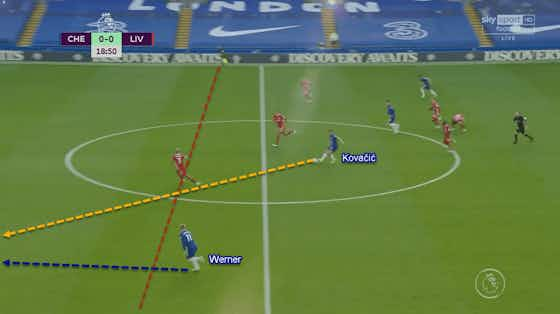

As mentioned before, Chelsea tried to attack more often from the left flank. This was partly because they wanted to utilise the German’s pace and on-ball ability in the final third. Apart from the aerial approach, Chelsea also tried to utilise him in transitional sequences. It means that they would quickly try to find Werner in the left flank/half-space and allow him to drive into the final third on his own.

In the second-half, Chelsea only used two attackers after Christensen’s red card. Werner — starting as a left-winger — moved to play as a left-sided striker in the last 45 minutes of the game. As a forward, Werner often drifted to the left side before getting the ball and driving into advanced areas.

Werner’s tendency after receiving the ball was driving to the central area; either horizontally in the final third or diagonally from the halfway line. In this way, he could use sharp dribbling ability before unleashing his stronger right foot to make a chance for himself. One of his inside movements even led to the 75th-minute penalty, in which Jorginho failed to capitalise.

Before we examine Chelsea’s pressing strategies, we need to know first about Liverpool’s attacking structure. In this game, Liverpool deployed a (lopsided) 3–4–3 shape with one of the midfielders dropping alongside the centre-backs. The full-backs were then given the task to provide the width, while the attackers tuck inside to play close to each other in between the lines. However, none of Alexander-Arnold nor Robertson played more advanced. This was probably to prevent Chelsea’s rapid wingers easily exploiting them in transitions.

Chelsea themselves defended in a mid-block 4–1–4–1. They used quite a compact structure and a rather high defensive line as well, but not as extreme as Liverpool’s. Chelsea also deployed a ball-oriented press against Liverpool’s midfielders; quite similar to their rivals to some extent.

In the ball-oriented press, one of Chelsea’s midfielders would step up from his position to press either Keïta, Henderson, or Wijnaldum. Basically whoever had the ball in the pivot space. The objective was to prevent the on-ball midfielder to control possession and force the ball to be played backwards. This tactic worked quite well, as Liverpool only managed to get 0.3 xG from five shots apart from Firmino’s one-off chance in the 14th minute.

After the red card, Lampard instructed his team to defend in a deeper 4–3–2 with Mount and Werner upfront. Sometimes this shape could also shift to a 4–4–1 with Mount dropping to the left-wing and Kanté drifting to the right flank. Chelsea also adjusted their defensive tactics by focusing more on protecting the flanks.

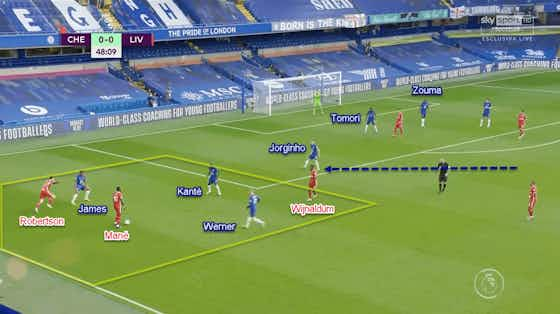

Due to the increasing aggression of Liverpool’s full-backs, Chelsea tried to defend the flanks harder. To do that, they would try to outnumber Liverpool’s players on the flank. The details were as follow:

The first player tasked to press was the ball-side full-back, who steps out from the backline. Then, he was supported by the ball-side central midfielder and forward. Sometimes, Jorginho — the central midfielder — could also join the flank press, particularly when the forward wasn’t around.

In the box, the centre-backs would stay to protect the goalmouth area. Another reason behind that was also to ensure Chelsea had more bodies inside the box if Liverpool were able to make crosses. Usually, Jorginho would be tasked to drop to the box and join the backline to add numbers in the penalty area. However, his energy was split because of his flank-press responsibility as mentioned previously.

Ironically, Liverpool’s first goal came from the failed flank press. They were unable to capitalise on the numerical advantage, thus allowing Firmino and Salah to create chaos in their left flank. Credits must also be given to Liverpool. That’s because their flank-to-flank approach successfully disrupted Chelsea’s defensive structure by pulling Zouma out of his position, and giving Mané enough space to score.

This match was much closer than the scoreline suggested. Both managers were able to cancel out each other with their tactics, especially in the first half. However, as some might say, tactics are only as good as the players. The men in red proved that by executing their decisions and actions better than the home side.

Christensen’s unnecessary rugby tackle, Arrizabalaga’s (another) howler, and Jorginho’s missed penalty were the proofs. Chelsea surely deserved a better result if those didn’t happen. But, football is a cruel sport. None are allowed to commit an error in this low-scoring game, let alone making three in 35 minutes. The Blues now have to bounce back with a win against Championship side Barnsley in the Carabao Cup this Wednesday.